Best Practices for Writing Unit Tests in C# for Bulletproof Code

By Steven McLintock onIn my experience, developers have a love hate relationship with unit testing. I don’t know if some find it tedious, or some just don’t see the value in writing code to verify if other code works.

I should elaborate. Unit testing is the art of writing code to verify if a unit of functionality in a software application is working the way it was intended to work. If the intention was to capitalize the first letter of a word, a unit test could verify that the first letter is capitalized and all the other letters remain untouched.

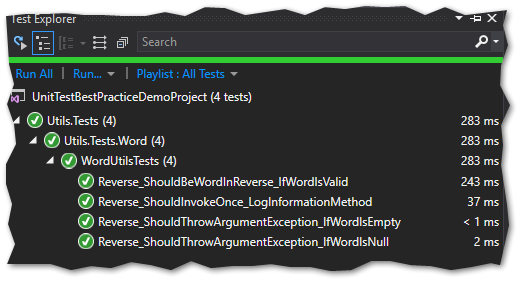

In my opinion, one of the benefits of writing unit tests in C# is the peace of mind of using the Test Explorer in Visual Studio to easily determine if all tests pass or fail, without having to worry if the last change you made to the code broke anything.

Choosing a Testing Framework

Testing frameworks enable us to decorate our unit tests with attributes such as (or similar to) [TestClass] or [TestMethod]. These attributes inform the Text Explorer in Visual Studio to recognize the class or method as a unit test and will execute the code to return a pass or a fail.

The most popular .NET testing frameworks are (at the time of writing and in no particular order):

- MSTest

- xUnit.NET

- NUnit

Choosing a testing framework is like choosing a car. Some offer high performance, some offer convenience, but at the end of the day, they all accomplish the same goal.

As far as I know, NUnit was the first popular test framework in the .NET community, trumping the feature set offered by MSTest (Microsoft’s testing framework) at the time. MSTest matched the feature set offered in NUnit (for the most part) and now MSTest is actually a great testing framework to use, considering it’s built right into Visual Studio. xUnit.NET is the new kid on the block, offering more features and an easier approach to writing unit tests focusing on .NET Core.

I wouldn’t spend too much time considering the testing framework to use in your project. If your project already implements a specific framework, use that one. If not, I would recommend doing a bit of research and decide on the one that’s right for you.

AAA (Arrange, Act, Assert)

Before we begin to unit test our code, it’s worth mentioning the **’AAA’ (Arrange, Act, Assert) ** approach to unit testing. This is common practice in the industry and enables you to write a unit test in a repeatable and understandable pattern.

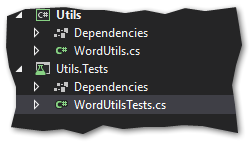

I’ll be using the class ‘WordUtils’ and the method ‘Reverse’ for the purpose of this article. The class has a constructor that will accept an instance of ‘ILogger’ for logging purposes. The method ‘Reverse’ will accept a string parameter and return the string in reverse. E.g. “mountain” will become “niatnuom”.

Arrange

We’ll begin the unit test by ”arranging” the objects you require to test a unit of code. This could be initializing a class, populating a local database with test data, or mocking an object using an interface (more on this later).

In the example below; the interface ‘ILogger’ is used to create a mock object to pass to a new instance of the ’WordUtils’ class:

// Arrange

ILogger log = Mock.Of<ILogger<WordUtils>>();

IWordUtils wordUtils = new WordUtils(log);

Act

We’ll “act” on this arrangement and invoke the unit of code under test. Usually, this means a specific method within a class is invoked by passing in a parameter (or multiple parameters) and storing the returned data in a variable.

In the example below; ”mountain” is reversed and the result is stored in the variable ‘result’:

// Act

string result = wordUtils.Reverse(“mountain”);

Assert

Finally, we’ll “assert” that the actual result of the invoked method is equal to our expectation.

In the example below; the variable ‘result’ should be equal to ”niatnuom” (”mountain” in reverse):

// Assert

Assert.AreEqual(“niatnuom”, result);

Naming Convention

Where as the concept of ‘AAA’ is a popular best practise, naming conventions tend to vary and are usually dependant on the developer; team and/or organization.

That being said, it’s a good idea to decide on a naming convention to apply to your unit tests for consistency and legibility.

My personal preference is to use the convention:

- The method under test (e.g. ‘Reverse’)

- A brief description of the scenario of the test (e.g. ‘ShouldThrowArgumentException’)

- The expectation of this scenario (e.g. ‘IfWordIsNull’)

public void Reverse_ShouldThrowArgumentException_IfWordIsNull()

{

...

}

This convention (or a variation of this) is great for viewing the Text Explorer and easily being able to determine what each unit test is without opening the unit test itself.

Test Initialize & Cleanup

If you are testing a method contained inside a class, you will likely need to initialize the class multiple times in each unit test. To save time, we can use the [TestInitialize] attribute in MSTest ([SetUp] in NUnit or use the contructor in xUnit.NET) to indicate that a method is to be used to create an instance of our class before each unit test is run.

We can also use the [TestCleanup] attribute in MSTest ([TearDown] in NUnit or implement the IDisposable interface in xUnit.NET) to cleanup our objects once all tests are finished.

In the example below; we can write the class initialization once and the class will be re-initialized before each test is run:

ILogger _log;

IWordUtils _wordUtils;

[TestInitialize]

public void Initialize()

{

_log = Mock.Of<ILogger<WordUtils>>();

_wordUtils = new WordUtils(_log);

}

[TestMethod]

public void Reverse_ShouldBeWordInReverse_IfWordIsValid()

{

string word = "mountain";

string reverseWord = _wordUtils.Reverse(word);

reverseWord.ShouldBe("niatnuom");

}

[TestCleanup]

public void Cleanup()

{

// Optionally dispose or cleanup objects

...

}

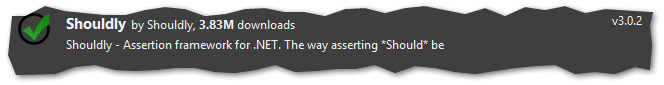

Shouldly Assertion Framework

I’m unable to stress enough on how the Shouldly framework will improve your unit tests. Shouldly enables a developer to write fluent assertions in their unit tests, making it far easier to understand the purpose and expectation of the test.

Check out the examples below with and without Shouldly:

With Shouldly

reverseWord.ShouldBe("niatnuom");

Without Shouldly

Assert.AreEqual(“niatnuom”, result);

Shouldly can also be used to determine if an exception is thrown and verify if the message is as you expect it to be:

[TestMethod]

public void Reverse_ShouldThrowArgumentException_IfWordIsEmpty()

{

string word = string.Empty;

Should.Throw<ArgumentException>(() => _wordUtils.Reverse(word))

.Message.ShouldBe("Please enter a word to reverse.");

}

I highly recommend integrating Shouldly into your unit tests to better understand the expectation of the test when you write it and when you revisit it at a later date.

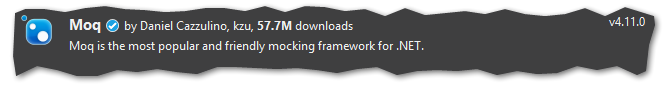

Moq Mocking Framework

The last topic I want to touch on is the ability to mock objects in unit tests. Why you ask? It is a huge benefit to be able to mock an object, such as a logging utility or a database, instead of invoking the object itself.

For example; if you were paying for a monthly plan at logentries.com, you definitely do not want each log triggered by a unit test to eat into your monthly limit. You also wouldn’t want to see production logs and unit test logs in the same log container. This is the same for database access layers, and is why we use mocking frameworks in .NET.

Using the popular Moq framework we can easily mock a class using it’s interface. This will enable us to use a mock of the logging utility in our unit test, instead of the logging utility itself:

ILogger log = Mock.Of<ILogger<WordUtils>>();

We can also verify if a mock object was invoked inside a method and the amount of times it was invoked:

[TestMethod]

public void Reverse_ShouldInvokeOnce_LogInformationMethod()

{

ILogger log = Mock.Of<ILogger<WordUtils>>();

IWordUtils wordUtils = new WordUtils(log);

string word = "mountain";

string reverseWord = wordUtils.Reverse(word);

Mock.Get(log).Verify(x => x.Log(

LogLevel.Information,

It.IsAny<EventId>(),

It.IsAny<FormattedLogValues>(),

It.IsAny<Exception>(),

It.IsAny<Func<object, Exception, string>>()),

Times.Once);

}